Estimates predict that private investment markets will grow to almost $6 trillion in the next four years.[1] Despite this explosive growth, participation by individuals, smaller family offices and wealth managers have remained low, with large institutions dominating this traditionally illiquid asset class and smaller investors facing significant barriers to entry – including long lock-in periods, illiquidity, high minimum investment requirements, difficulty gaining access to the best managers, and high service fees. It is only in recent years that new and more agile fund managers have begun to break down barriers and open the door to these markets for smaller investors. However, an element of mystery remains. What are private markets, how do they work, what are their upsides, their downsides, and the long-term implications?

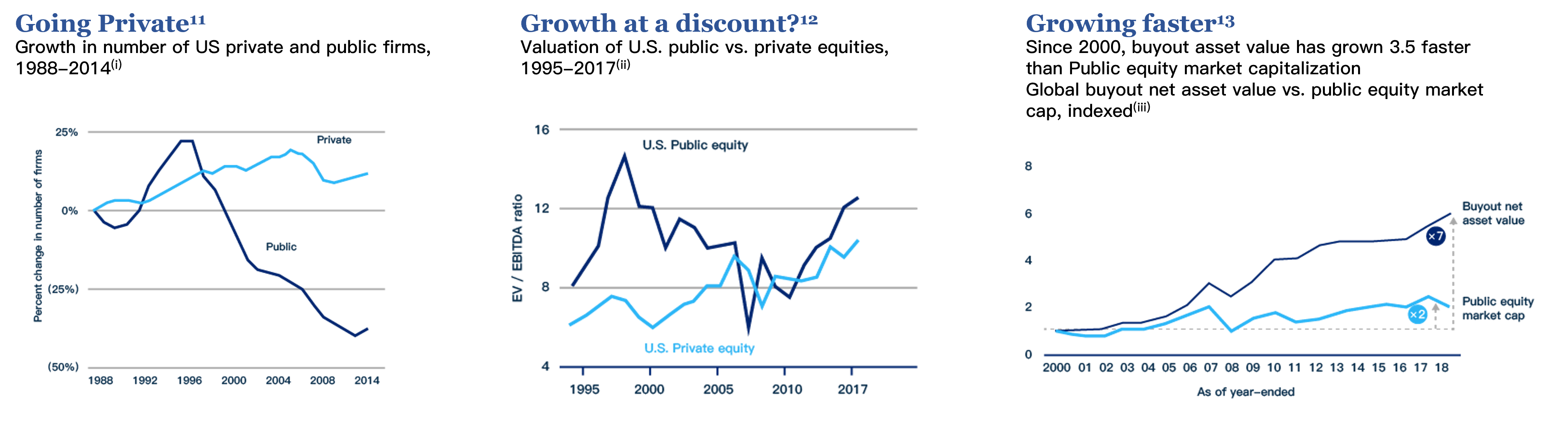

Whilst the Covid-induced volatility offered some opportunity to the public to generate outstanding returns, these type of buying opportunities are hardly sustainable on a consistent basis, and in the long-term are challenging to rely on for portfolio construction. As companies stay private for longer, economic growth is increasingly happening outside of public markets.[2] At the same time, after an exceptional bull run in the public equity markets over the past ten years, long-term estimates point to lower expected returns in the public markets in the coming decade.[3] As such, investors may now need to add additional sources of high-returning investment products to their portfolio to achieve the usual 7% long-run return that investors typically target.[4]

As private markets have been shown to consistently outperform public markets, on average by 4-6%, considering an allocation to private markets is now a viable alternative for investors looking for long-term capital appreciation (i.e. a rise in portfolio value).[5]

Read on to discover more about private markets – and how you may capture the opportunities they present.

Q1: I’ve been rather successful with my public market investments in the past two years - why should I add alternatives to my portfolio now?

The Covid-induced market corrections in 2020 prompted many existing and new investors to double down on public markets – but, whilst their efforts were often handsomely rewarded, public markets are now at or near their all-time highs, with many public stocks (and bonds) selling at elevated valuations.[6]

As private wealth continues to grow, with more younger investors, female investors, emerging-market entrepreneurs, and a host of other new investors entering the investment market, those outsized returns are becoming harder to generate, and even in the best of times, buying opportunities during market corrections, such as those seen in 2020, are not sustainable long-term.[7]

Additionally, frustration with traditional asset classes is exacerbated by volatility in public markets that is now baked-in, with shares rising and falling on news bites, rumours, and minor fluctuations in overall economic conditions. These combined factors make it doubly hard for smaller investors to create long-term value, as the time-consuming tasks of persistent vigilance and acute market timing are now required to achieve the best results.

Conversely, the non-public (i.e. non-traded) nature of alternative investments allows for volatility to remain relatively subdued. The private equity market is estimated to reach US$5.8T by 2025 and it has shown great resilience to recent downturns, including the Great Financial Crisis of 2007-09 and the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020-21.[8] The American Investment Council’s Public Pension study report of 2019 indicated that private equity continues to lead all asset classes in long-term investment performance, with private equity’s median 10-year annualized net return of 10.2% outperforming public stocks at 8.5%.[9]

In addition, historically, private markets’ highest returning vintage years tend to follow recessionary periods, particularly when selecting the top managers, who can deploy capital fast and opportunistically. [10]

Finally, tomorrow’s unicorns may never go to IPO. Private companies are staying private longer and growing faster at lower valuations. Their eventual success may not be accessible via public markets. This means that investors who ignore private markets now may be limiting their portfolio’s growth potential.

(i ) Lines show the percentage change in the number of private and public firms in the U.S. since 1988.

(ii) U.S. public equity valuation exclude financials and are based on the capital IQ database of U.S. stocks. Private equity valuations are based on an annual average of leveraged buyout purchase prices and are net of fees. EV/EBITDA is a valuation metric determined by dividing a company’s enterprise value (EV) by its earning before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA).

(iii) Buyout net asset value based on unrealized value.

Q2:How do you define private markets?

Whereas ‘public markets’ refers to investment in securities of companies listed on public exchanges, ‘private markets’ refers to investments in privately owned companies that are not publicly traded.

Many private companies will remain private during their whole existence, whilst others may eventually list on public markets through an initial public offering (IPO). While the nature of privately held businesses limits liquidity, it also gives rise to ‘illiquidity premium’, i.e. the compensation an investor earns in exchange for giving up liquidity, which is a defining feature of private markets.

The term ‘private markets’ is also often used interchangeably with the term ‘alternatives’ or ‘alternative investments’. While there is no set definition for alternatives, with the term originating decades ago, it is typically used to denote ‘alternatives to traditional stocks and bonds investing’ and often includes other asset classes such as hedge funds or commodities. That said, what sets private markets apart is the opportunity to earn the illiquidity premium. Hedge funds typically hold publicly listed, liquid securities as underlying investments, and as such many investors do not consider hedge funds as part of traditional private markets. Equally, commodities are also widely publicly accessible via ETFs and as such rarely ever form part of institutional private markets portfolios.

In terms of security types, private markets investments fall into two broad categories – equity and debt.

Private equity is equity capital invested in private companies and where investors aim to increase a company’s value and sell their stake at a later stage through a trade sale, buyout, recapitalization, or through listing the company via IPO.

Private debt investment targets the ownership of credit issued by private companies that either seek more flexible or economical financing arrangements or are unable to raise capital from commercial lenders. Private equity investment represents the majority of investments in private markets, eclipsing private debt in 2020 by a ratio of approximately five to one. [14]

Private equity is often synonymous with leveraged buyouts, however, it can also denote privately held equity investment in earlier stage companies such as growth buyouts, and even other asset classes, such as infrastructure and real estate. Private debt investments follow a similar pattern – whilst most private lending targets mature companies (often held by buyout managers), in recent years private debt managers lending to real estate, infrastructure and even venture capital portfolio companies have also appeared.

Q3:How is a private market investment different from a public market investment?

Investment in publicly listed companies is driven by the quarterly reporting cycle and as such, it often incentivises management teams to prioritise short-term objectives over companies’ long-term value creation and growth opportunities.

At the same time, publicly available information services create fewer opportunities for astute managers to find overlooked value. Wide public access also means that investors can enter or exit to a liquid market, meaning transactions can be executed quickly.

In contrast, private market investments remain largely closed off to the millions of investors who populate the public markets landscape and are therefore not subject to public scrutiny of their performance. This also means there is a much lower number of potential buyers to whom companies can be sold to and exits can take time and planning. Whilst this illiquidity feature is a source of risk that is remunerated with the illiquidity premium, there are several advantages to companies and management teams:

- The lack of quarterly media scrutiny allows management teams to focus on long-term value creation opportunities, instead of short-term share price movements.

- The relative illiquidity incentivises managers to work hard to create value, as opposed to just waiting for price appreciation in the public markets. If private markets managers are wrong or make a mistake, they cannot just sell the company on the public market – this incentivises more thorough underwriting and due diligence and explains some of the relative outperformance of private markets vs. public markets fund managers.

- Due to the relatively limited amount of public information, the proprietary sourcing capabilities of private markets managers, coupled with their execution capabilities (i.e. access to top industry advisors, experienced deal professionals who are experts in the targeted industries, dedicated value creation teams for various functional areas, such as marketing, sales, HR, etc.) provide an opportunity for true alpha generation.

This dynamic results in several features that distinguish private markets from public markets:

- Control/more direct involvement: Private market investment managers often take a direct management role in the companies in their portfolios – playing a leading role in the development of the businesses and adding significant value over the investment period. Often, managers will invest their own money in the funds they raise, using their personal stake as a bellwether for the decisions and actions they take.

- Longer time horizons: The length of time required to execute value creation plans and build value require that capital remains invested longer relative to public markets. Undisturbed by public scrutiny, private markets managers seek to steadily build value over several years before eventually exiting the investment.

- Illiquidity: On average, investments are locked-in for an investment period of five years but may be held for longer.

Somewhat shielded from the public eye and public market volatility, private markets are seen as a source of uncorrelated return with a reduced volatility profile and greater opportunity for excess returns. Investors therefore consider private markets in the pursuit of higher long-term returns than they may achieve through public markets alone.

Q4:Alternatives seem to have an attractive return profile and features, so why has private wealth’s allocation to private markets been subdued?

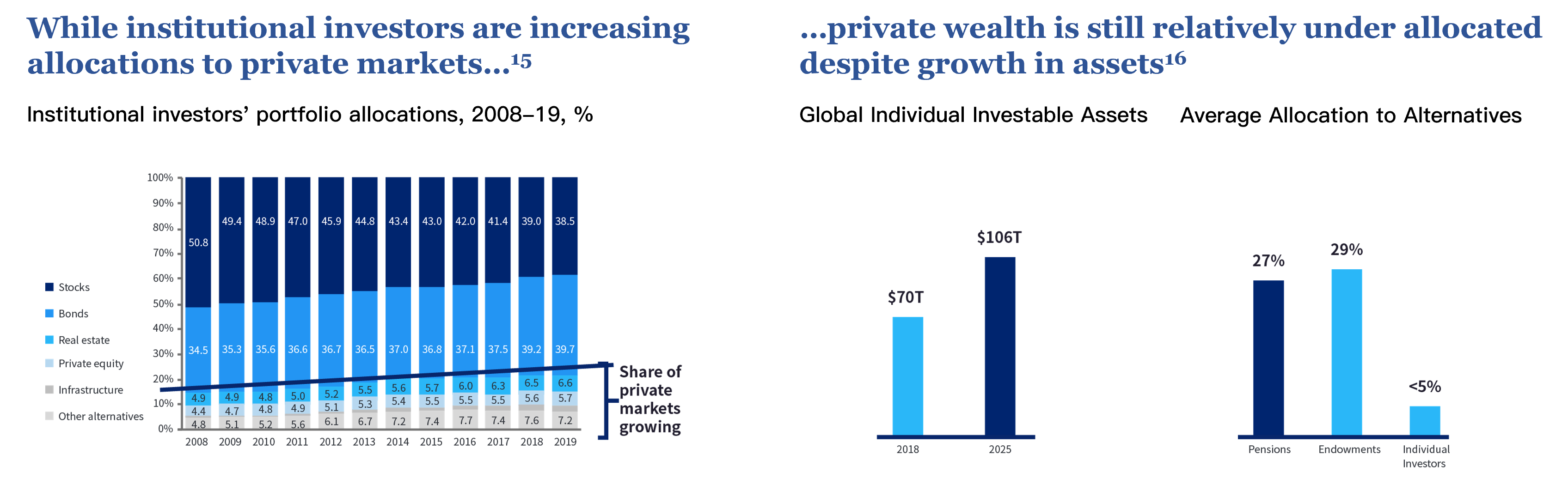

Even though global individual investable assets are predicted to expand from US$70T in 2018 to US$106T by 2025, private wealth remains under-allocated to private markets compared to institutions.

The reasons for this disparity are three-fold:

- Firstly, due to the illiquidity, longer lock-in periods, and limited opportunities to exit, private market investments are more complicated than public markets. Regulations are in place to ensure only accredited investors enter these markets.

- Secondly, specialised skills are needed to understand complex documentation, conduct due diligence, select the best performing managers, and then gain access to them. Institutional investors have historically built large teams to perform this time-consuming and expensive work, but it has typically been beyond the capabilities of individuals and even smaller family offices and wealth managers.

- In addition, the same due diligence, KYC, anti-money laundering and other regulatory checks apply to small and large investors alike. This means the admin burden on private markets managers and private banks is the same, regardless of whether the investor is investing $100k, $1million or $100million. This has made it economically challenging to accept smaller investors and has driven managers to set minimum investment sizes, often in the range of $10-20million.

Simply put, high entry costs, due diligence requirements and regulatory hurdles have long kept private markets out of reach to private wealth. It is only recently that more agile managers have stepped forward to leverage technology to remove these hurdles and create access with lower entry tickets, easy-to-understand investment data and regulatory support to satisfy investor needs.

Q5: How do I get started, and what are some of the pitfalls in private market investing?

Before beginning to build a private market strategy, investors should consider their specific needs:

— return requirements

— investment horizon, i.e., how long they are prepared to wait to achieve their return requirements

— liquidity requirements and potential cash flow pressures during this time

They should also consider how well the special features of private markets complement their existing investments, ability to make individual investment decisions, potential tax implications and other restrictions or constraints.

With parameters set, it is important to first understand what the available private markets strategies are, their characteristics and their value-add to the existing portfolio.

Just like public markets, one can run a concentrated or a diversified portfolio, depending on the level of conviction. Whilst selective fund-picking may be appropriate for those well-versed in private markets strategies, for those starting out, diversification may provide downside protection while retaining upside exposure.

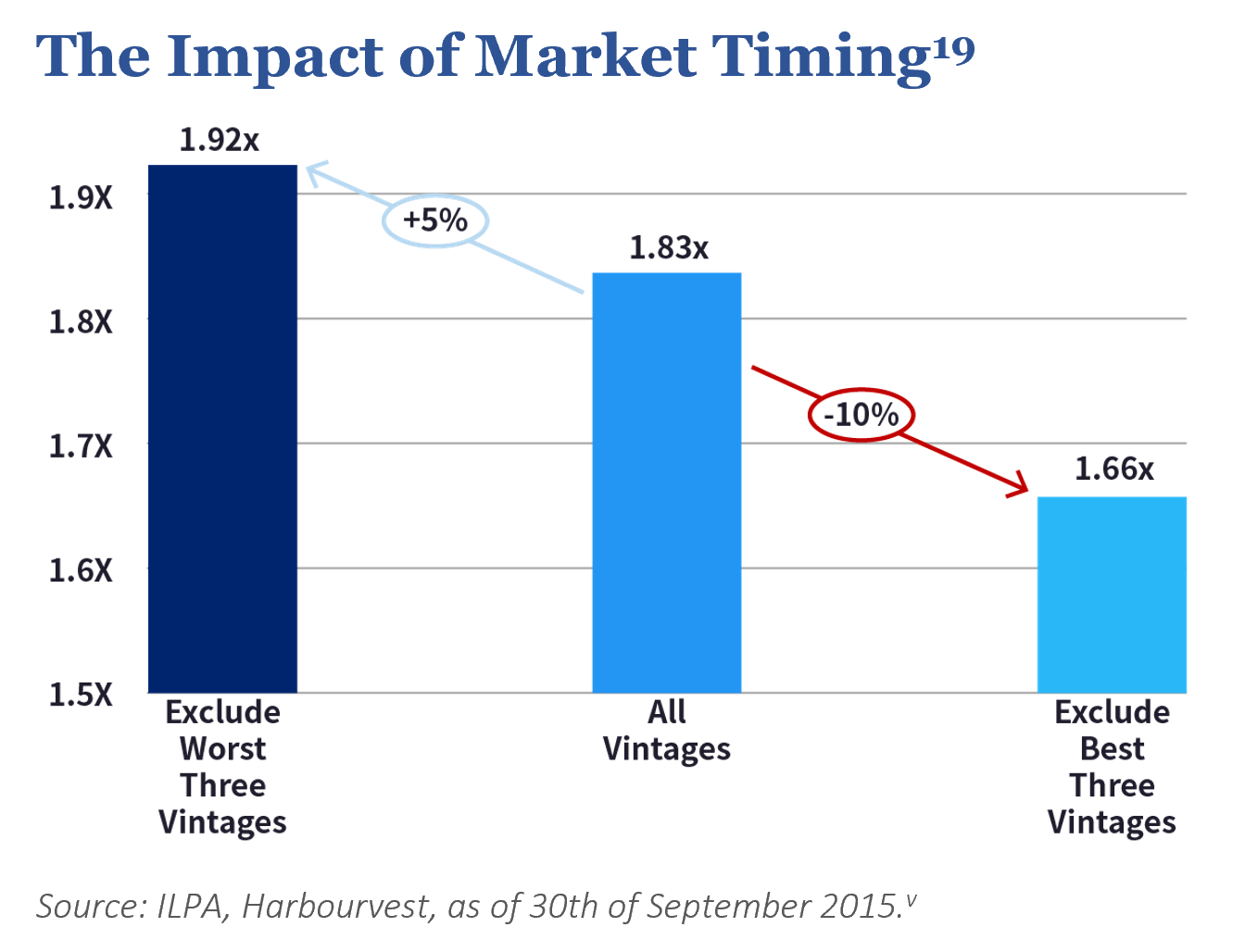

Private markets investing is a long-term strategy, and as such, some of the common pitfalls have to do with not fully grasping the long-term nature of the product, trying to time a market than cannot be timed, having a concentrated exposure to certain vintage years, strategies, sectors, or geographies as opposed to investing consistently and creating a diversified portfolio, and exiting a fund too early when returns take time to generate.

These issues are particularly pertinent in times of market corrections. While private markets can never be fully insulated from public markets, they have been shown to be less correlated. This limited correlation is a result of the illiquid and long-tern nature of the asset class – meaning one must resist the urge to try to treat the illiquid, long-term asset class as a short-term and liquid one by trying to exit too soon. According to research, giving in to the urge to stop or significantly alter fund commitments in times of public market stress is likely to lead to future portfolio underperformance. Furthermore, trying to time the market is impractical given that private funds deploy capital gradually.[17]

Q6: What private markets strategies are there to choose from?

Private markets strategies can be segmented in several ways, the most typical terms used are as follows:

Based on the access route:

– Primary funds: the classic private markets fund structure where investors (called Limited Partners or LPs) commit capital to a newly formed, closed-ended blind pool during their fundraising phase, which the manager (called the General Partner or GP) then invests into portfolio companies. Primary funds can be investing across any of the strategies listed in the ‘Strategies’ section below, which will drive target returns.

– Secondary funds: fund type set up to purchase the interests of investors who wish to exit an already closed and operating fund of prior vintage years. This allows for an earlier exit date and possibility of cash realisation. Private equity strategies are by far the largest target for secondary funds, however in recent years secondary funds targeting private credit and other strategies have been set up as well. Buyout secondaries funds target returns a few percentage points below buyout returns, however due to the significantly reduced blind pool risk, they may offer an attractive risk-adjusted return.

– Co-investments: a concentrated investment wherein a Limited Partner makes a direct equity investment into a company alongside the General Partner. Co-investment strategies provide an opportunity to double down on a portfolio company that the investor finds particularly attractive and wishes to gain additional exposure to. This is a strategy typically used in buyouts and targeting buyout returns, and it has some upside, as most co-investments are offered on a no-fee/no-carry basis. This strategy has a short (immediate) drawdown period, and whilst it can take 4-6 years to achieve a realisation, it is still shorter duration product vs. a typical commingled fund.

Based on asset classes/strategies:

– Venture Capital: typically minority investments into start-up and early-stage private companies, targeting 25%+ net annual return. Note: Net of annual management fees and performance fees (carried interest)

– Private Equity: umbrella term referring to control ownership of private company shares, can be further segmented by stage of company development:

- Growth: companies with rapid growth potential and usually positive cash flow, typically targeting an annual return of 20-25%.

- Buyout: strategy that typically takes control of mature, often good companies with improvement potential, with the help of fund equity as well as external leverage, improves company performance, uses the cash flow of the improved business to pay down debt and sell the improved company for a profit. This strategy is typically targeting net annual returns of 15-17%+.

- Distressed Capital: problem companies with the potential for successful turnaround, returning 15-20% net on an annual basis.

– Private Credit: ownership of credit issued by private companies to raise capital. There are sub-sets within this security class:

- Senior debt: usually secured debt and with priority over junior debt, targeting a 5-7% net return annually on an unlevered basis.

- Direct lending/unitranche: a combination of several tranches of senior secured and unsecured debt, often used to finance the entirety of the debt stack in leveraged buyouts (LBOs), typically targeting a 9-10% net annual return.

- Subordinated debt/mezzanine: also called ‘junior debt’, with lower priority for repayment than senior debt. Often the riskiest portion of debt in a leveraged finance transaction, with equity participation rights (warrants) attached, and as such net annual target returns are ~10-12%.

– Real Assets: typically the term used for asset classes such as infrastructure, real estate, and others with physical substance such as timberland.

- Real estate: strategy that uses the fund to acquire, develop, improve, and operate properties, which can then be sold on for a profit. Depending on the strategy, net annual returns are high single-digit/low-teens.

- Infrastructure: typically control equity investments in infrastructure assets, such as essential utilities (gas, electricity, water), transport (airports, ports, toll roads, railroads), communications (cable and satellite networks and mobile phone towers), and social infrastructure (schools, hospitals, prisons, etc.). Net annual target returns are in the low teens.

Q7: What are the features of a successful private markets portfolio?

When it comes to portfolio construction, each investor will have unique return expectations, risk tolerances, liquidity needs and investment capabilities. That said, successful investment programmes of the best institutional investors have been shown to have the following characteristics:

- Looking for and having the ability to access the top-tier funds – while past performance does not guarantee future results, top performing funds have been shown to persistently outperform public markets significantly

- Fully diversifying across the investment matrix – strategies, geographies, sectors, manager types and sizes. Exposure to risk is typically mitigated by the selection of complimentary investments – higher risk, such as venture capital, may be offset by lower risk, such as private credit or real estate. Note that this balancing act may correlate with the level of expected return – higher risk potentially coming with higher return and vice-versa.

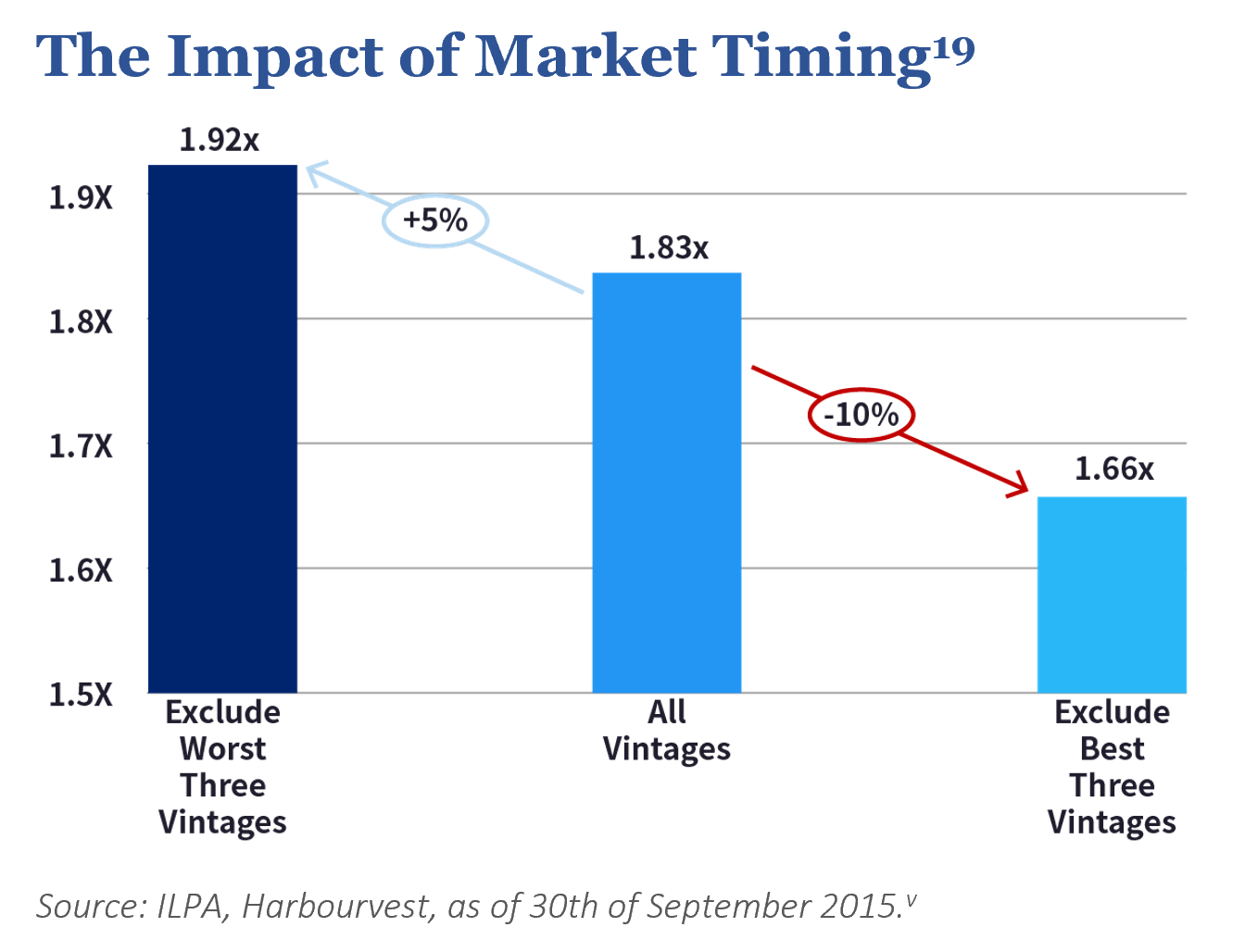

- Deploying consistently over an extended period – avoiding concentrations into high or low performance years and attempting to create balance and consistency. Most portfolios will contain assets of widely differing vintage years and exit timing. A veritable galaxy of external factors can make some vintage years better than others – this includes the state of the economy, public and private market environments, and conditions within a particular industry – but there will always be a continual exodus of investments as funds retire. Well-maintained portfolios will replace these retiring investments with new ones without pause, to retain an elevated level of consistency. However, some investors may attempt to time the market to achieve better results, opting to wait out the period between exit and new entry. Research shows that uneven investing has been shown to achieve lower returns than staying invested regardless of economic conditions.[18]

(v) Includes all HarbourVest fund/account primary partnership commitment gross returns from 1992 – 2011. Past performance is no guarantee of future returns.

Although it is impossible to guarantee what the investment and exit environments will be like over the extended life cycle of a typical private equity fund, the data reveals that outperformance in private equity is persistent and that top performers remain top performers regardless of general market conditions.

Investors seeking optimal returns should therefore take the time to research and select the best fund managers for their individual and long-term investment goals.

Q8: How do the timelines and cash flows work? What is the J-curve?

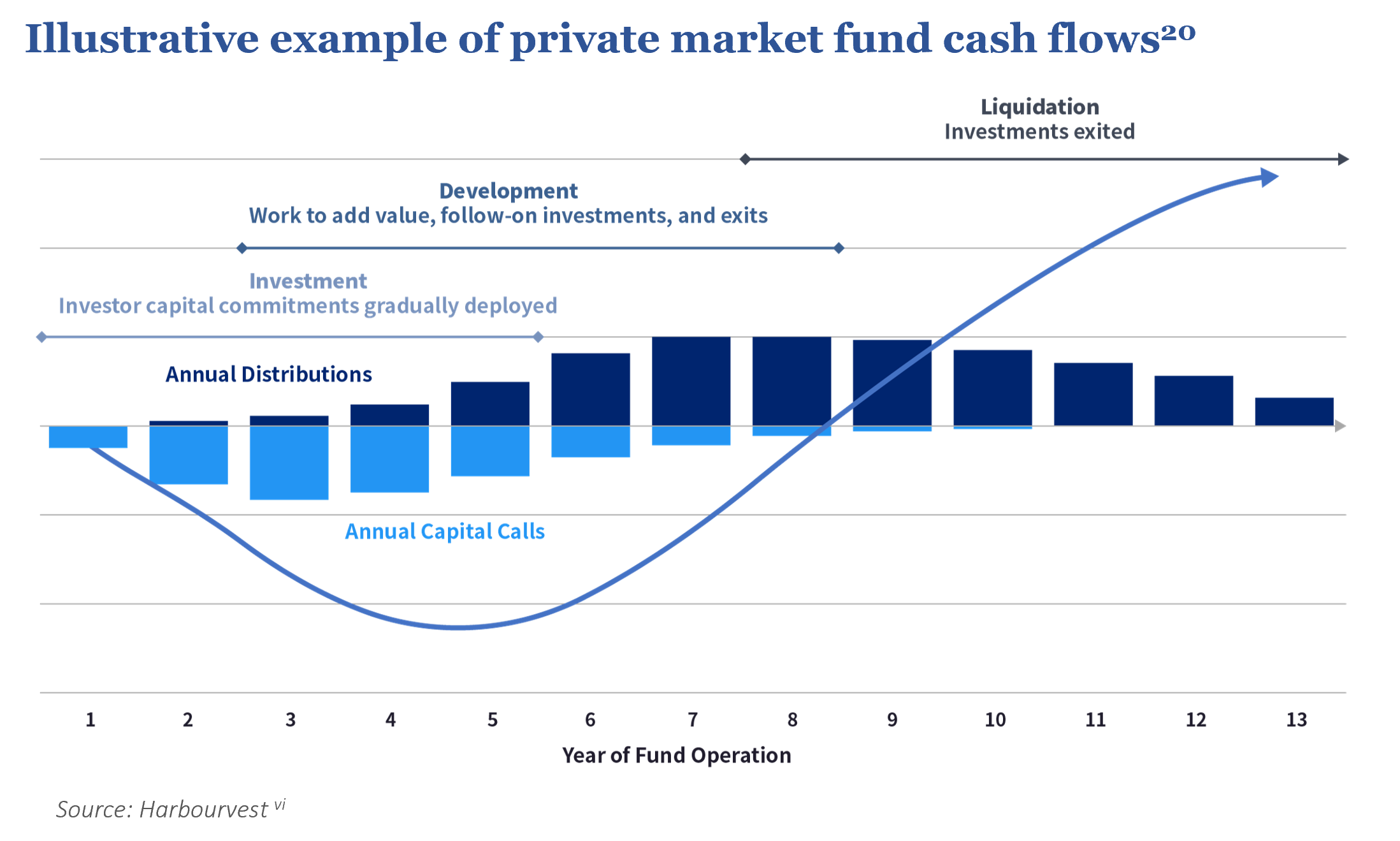

Private market investment horizons are usually longer-term.

On average, funds take 4-5 years to invest the fund, i.e., find, conduct diligence, and buy suitable portfolio companies, and then each portfolio company is held for 3-5 years, with improvements and value creation initiatives carried out before the company is sold. As such, it can take 3-5 years before investors receive their first distributions, with the bulk of distributions coming in years 5-7, and the tail-end of distributions following in years 8-10.

To fund this process, investors in private market funds agree to “commit capital”, which is effectively the total investment amount throughout the life of a fund. Investors are legally obliged to wire this money when requested by the manager. As managers identify and sign agreements to purchase companies, investor commitments are drawn down (i.e., cash is requested) on an as-needed basis to fund the company purchases, pay management fees and other expenses. The fund manager typically gives investors 7-10 days’ notice of a drawdown. Investors total commitment is drawn over years, as opposed to at once. However, investor withdrawals are not possible, so a careful consideration of liquidity requirements is advisable.

The fund managers will aim to maximize returns for investors by carrying out the improvements in the purchased portfolio companies. This can be both operational improvements, as well as an acquisition strategy to grow the businesses. As investments mature and the value creation plan is executed, the fund manager will look to ‘exit’, i.e., either sell the business to a strategic or financial buyer, or even IPO (i.e. sell the stock to the public markets). Investors then receive their share of the net proceeds pro-rata to their investment.

As the chart below shows, in the early years management fees and capital calls are made to fund company purchases. It is then followed by potential distributions in later years as value creation plans are realised, and thus, investor cash flows tend to be negative in the early years of a fund and turn positive later in the fund life as underlying investments are sold – this is called the J-curve effect.

(vi) This example is shown for illustrative purposes only and is intended to demonstrate the mechanics and cash flows of a private equity fund. It is not intended to predict the performance or cash flows of any specific fund and should not be construed as predicting the future. The actual pace and timing of cash flows of a private equity fund are highly dependent on the fund’s investment pace, the types of investments made by the fund, and market conditions. Private equity investing involves significant risks, including loss of the entire investment.

That said, investors wishing to enjoy returns from private capital investment, but who do not have the desire to wait many years to receive them, may consider a secondary investment structure. This allows investors to buy an interest in a previously raised fund, and it occurs when a third-party investor sells or exits all or a portion of their fund commitment prior to the normal liquidation period of the fund.

This practice has the triple benefit of allowing prospective buyers to gain greater visibility of the underlying portfolio companies, possibly buy-in at discount, and secure any returns sooner, as the underlying assets are typically more mature and closer to realisation.

Q9: How do I choose the best manager for my needs?

Investors having got to this part of the paper may already be a little overwhelmed with all the detail and considerations required to invest in private markets.

For those who are attracted by the promise of private markets, but who do not have the considerable time, resources, and expertise to conduct the necessary due diligence to invest in individual funds, there is the option to invest in private markets via a manager of managers. This manager-of-managers, or ‘fund-of-funds’ approach sees the investor appoint one manager to oversee a pool of managers who in turn, manage and develop the underlying assets in the portfolio. It is a way to get the best of both worlds – as the investor only needs to select one manager, who then in turn will select the underlying private markets managers. The process is streamlined and efficient, suitable for investors who find the necessary due diligence to select individual fund managers too costly and time-consuming.

Naturally, investors should look for managers who have the necessary expertise to manage the assets, the skills to add value to the companies in the portfolio, excellent analytical abilities, transparent and competitive fees, as well as satisfactory terms and conditions. Selecting an experienced fund-of-funds manager with access to top-tier private markets managers should still allow the investor to obtain the desired portfolio diversification and potential long-term benefits, with just one investment.

Conclusion

In recent years, allocation to private markets has become a realistic option for many sophisticated, high-net-worth individuals, as well as smaller family offices and wealth managers. It is no longer an area reserved for the giants. With an increasing number of companies staying private and public markets representing lower returns in exchange for higher volatility, ignoring private markets is no longer a viable option for true value creation. If the growth trends and resilience of private markets over the last two decades are any indicators, future private wealth creation may be best served looking outside of traditional public markets and considering adding private markets to investor portfolios.

Sources:

[1] Deloitte, The growing private equity market (05 November, 2020) (accessed November 2021)

[2] Hamilton Lane, Broader Horizons: The Case for Private Markets Investing (06 May, 2021) (accessed November 2021)

[3] Charles Schwab, Why Market Returns May Be Lower and Global Diversification More Important in the Future by Veeru Perianan (03 May, 2021) (accessed November 2021)

[4] Callan, Risky Business Update: Investors Face Additional Challenges amid Increased Uncertainty by Julia Moriarty (27 January, 2021) (accessed November 2021)

[5] McKinsey, A year of disruption in the private markets: McKinsey Global Private Markets Review 2021 ( April, 2021) (accessed November 2021)

[6] BNP Paribas, All-time highs on equity markets in spite of (almost) everything – Investors’ Corner (04 April, 2021) (accessed November 2021)

[7] Capital Group, What Past Stock Market Declines Can Teach Us (accessed November 2021)

[8] Deloitte, The growing private equity market (05 November, 2020) (accessed November 2021)

[9] American Investment Council study, New AIC Pension Study: Private Equity Delivers Highest Returns For Public Pension Funds (27 July, 2019) (accessed November 2021)

[10] Bite Investments, PE fund vintages launched during downturns tend to outperform (19 Jan, 2021) (accessed November 2021)

[11] BlackRock Investment Institute, with data from U.S. Census of U.S. Business; Doidge, Karolyi and Stulz (1988 2012), and Wilshire Associated (2013 2014), October 2017 (accessed November 2021)

[12]BlackRock Investment Institute, with data from S&P Capital IQ Goldman Sachs, October 2017 (accessed November 2021)

[13] Bain Global Private Equity Report 2020, based on Preqin, World Bank, March 2021 (accessed November 2021)

[14] McKinsey, A year of disruption in the private markets: McKinsey Global Private Markets Review 2021 ( April, 2021) (accessed November 2021)

[15] McKinsey Global Private Markets Report, April 2021, based on CEM Benchmarking (accessed November 2021)

[16] SEC, Blackstone, November 2019 based on the 2018 CapGemini World Wealth Report For allocations 2016 Willis Towers Watson Global Pension Assets Study 2016 National Association of College and University Business Officers Money Management Institute, “Distribution of Alternative Investments through Wirehouses Allocations shown are for US Pensions and US University Endowments” (accessed November 2021)

[17] HarbourVest, It’s a Marathon, Not a Sprint: Consistent Investing for Long-Term Performance (2020) (accessed November 2021)

[18] Burgiss and Harbourvest data as of 2019, includes all Harbourvest fund between 1992-2014 (accessed November 2021)

[19] ILPA members’ conference Boston, Portfolio Management: Investing in Different Market Environments by Gregory Stento, Managing Director, HarbourVest Partners (accessed November 2021)

[20] HarbourVest, What are cash flows like for private market funds? (accessed November 2021)

Disclaimer: All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, Bite Asset Management. The facts of this article are believed to be correct at the time of publication but cannot be guaranteed. Please note that the findings, conclusions and recommendations that Bite Asset Management delivers are based on information gathered in good faith from both primary and secondary sources, whose accuracy we are not always in a position to guarantee. As such, Bite Asset Management, can accept no liability whatsoever for actions taken based on any information that may subsequently prove to be incorrect.

This document has been prepared purely for information purposes, and nothing in this report should be construed as an offer, or the solicitation of an offer, to buy or sell any security, product, service or investment.